A version of this article was originally published in Urban Land Magazine on January 21, 2020.

No more natural gas in new homes as of January 1, 2020. That’s the directive that Berkeley, California, handed to housing developers in July 2019, and it’s one that a growing number of cities are poised to deliver.

No more natural gas in new homes as of January 1, 2020. That’s the directive that Berkeley, California, handed to housing developers in July 2019, and it’s one that a growing number of cities are poised to deliver.

As governments work to limit their climate impacts, they’re driving changes that could substantially affect developers—and a new crop of buildings powered completely by electricity could be one result. That’s why lawmakers in Berkeley made international news when they banned the installation of natural gas lines in new low-rise homes, including new single-family homes and townhouses. Developers need to be ready for other municipalities to follow suit.

More than 50 California cities are considering measures like Berkeley’s, and that could be the beginning of a larger wave.

Through its Ready for 100 campaign, the Sierra Club secured commitments from nearly 200 cities to meet their power needs with all-renewable energy. One of the steps toward achieving that goal is eliminating the use of natural gas.

Some cities, like Sacramento, are using carrots rather than sticks. The Sacramento Municipal Utility District in 2018 partnered with national homebuilder D.R. Horton to build two new all-electric projects in a deal that includes rebates to developer D.R. Horton of up to $466,000 for 104 homes. Other developers have another 400 all-electric homes planned.

With the national housing crunch grabbing headlines, much of the debate has focused on residences, but the push for 100% electric power will also affect office, retail, and industrial construction. “Building electrification” is seen as a key step in decarbonizing the built environment because buildings account for 12% of total US greenhouse gas emissions, according to the US Environmental Protection Agency.

Even some big companies with a stake in the status quo are getting on board. For example, Pacific Gas & Electric, whose natural gas network generates $4 billion in annual revenue, sent a public relations executive to the Berkeley City Council meeting in July 2019 to declare its support for the initiative.

Getting to Net Zero

Several countries, including Sweden, Norway, France, and the United Kingdom, already approved laws mandating net-zero greenhouse gas emissions targets. Net-zero-energy buildings—those that use no more energy than they generate—have been a key part of those discussions. Denmark has made a commitment to eliminate fossil fuels from heating by 2050. The Netherlands plans to stop using natural gas completely by 2050.

In the United States, climate-conscious California cities have been at the forefront of the push for an all-electric future.

- Los Angeles announced a goal to make all buildings in the city net-zero energy by 2050.

- The Silicon Valley Clean Energy board, which includes officials from 13 localities, in December 2018 announced a “Decarbonization Roadmap” that includes a focus on “all-electric building and design incentives, installing more electric vehicle-charging infrastructure, as well as retrofits from gas to high-efficiency electric water heaters.”

- In San Francisco, which has a goal of net-zero emissions by 2050, a seminar in May 2019 on all-electric housing drew a cross section of city staff, developers, and industry consultants. A local nonprofit housing developer delivered a presentation pointing to five trends driving the heightened interest in building electrification. They provide a useful roadmap of the case for going all electric.

How to Attain All-Electric

1. Social Responsibility

First, building electrification can meet public-policy and consumer goals for energy-efficient multifamily projects, says Joanna Ladd, senior project manager of Chinatown Community Development Center.

“What people want is social responsibility,” says Eric Rohner, national practice leader for renewable energy at accounting firm Moss Adams. “Would you even think of putting a building together that isn’t energy efficient, that doesn’t have LED lights, low water utilization, and doesn’t include smart meters or at least the ability to be upgraded to smart energy technologies?”

“Even if that means higher prices, clients are often willing to pay more for those measures, and in many cases, their employees are demanding them,” he adds.

2. and 3. Cost Competitiveness in Development and Operations

The upfront cost to go all electric is about the same as for natural gas or other fossil-fuel sources, Ladd says. Improved technology is part of the reason.

All-electric buildings using heat pumps are less expensive to construct and operate than buildings using natural gas, according to The Economics of Electrifying Buildings, a report from the Rocky Mountain Institute that analyzed scenarios in four cities.

Heat pumps, which move heat into or out of buildings using electricity, are much more efficient. “In many scenarios, notably for most new home construction, we find electrification reduces costs over the lifetime of appliances when compared with fossil fuels,” according to the report.

4. Installation and Maintenance

The installation and maintenance of all-electric systems are relatively easy and low cost, according to Ladd.

5. Consumer Demand is Growing

That includes demand from corporate users looking to keep their carbon footprints in check as they get ready for regulations that will require them to disclose sustainability data.

“If you are working with a big blue-chip company, your client will have to report on the property’s annual emissions,” says Barny Evans, head of the sustainable places, energy, and waste team at UK-based design and engineering firm WSP, in an interview published on the firm’s website. “Electric buildings are reporting lower carbon every year as electricity production itself becomes more efficient and lower carbon.”

Government Incentives

Projects are more likely to pencil out in regions where energy costs, politics, and infrastructure are most supportive. High Point, a Seattle public housing redevelopment project built without gas lines, won ULI’s Global Award for Excellence in 2007—and saved the US Department of Housing and Urban Development more than $500,000 in utility fees annually.

Tax incentives make the economic case for all-electric buildings more appealing, especially for buildings that combine all-electric construction with renewable energy sources. Developers may be able to get a 30% federal tax credit for installing solar panels, and even if they can’t monetize the credit directly, they can partner with leasing companies that install and own the panels while sharing the cost savings with users.

Experts at Seattle- and San Francisco-based design firm Mithun, which designed the High Point project, say that building without gas can be cost-neutral or even cheaper than traditional construction.

Five multifamily housing projects that the firm is working on in San Francisco are delivering savings from technology advances in heat pumps and other products, as well as from federal tax credits for affordable housing that are tied to energy efficiency targets. Avoiding both gas-equipment and gas-related code requirements also produces savings.

“The fossil fuel-free future is arriving, starting now,” says Anne Torney, a Mithun partner. “With solid benchmarking data we’re compiling over the next three to five years, we anticipate even more evidence-based design iterations from project results and experience that can make all-electric, sustainable design a first choice.”

Even in the US northeast, where biting-cold winters have in the past made heat pumps using older technology uneconomical, builders are finding ways to go all electric.

H.A. Fisher Homes is building a nine-unit condominium project to net-zero-energy standards in Warwick, Rhode Island—and betting that buyers will be willing to pay the 5%–7% premium needed to cover the costs of energy-efficient materials. (The concept of all electric being less expensive is also highly local. and for this project the cost isn’t fully offset.) The project is eligible for up to $50,000 in incentives from National Grid, the local utility.

Counterpoints: Consumers, Cooking, Grid

Despite the push to lower carbon emissions and the availability of high-performance electric induction cooktops, natural gas remains in high demand for cooking across much of the United States.

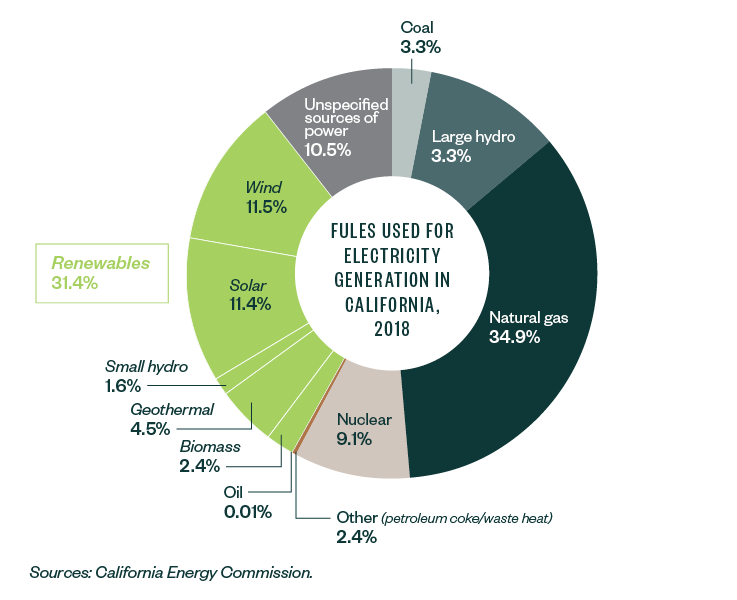

Gas also remains a staple energy source, providing heat for about 56 million US households, or 44% of homes, and demand is still rising. “Oil and coal already have peaked; natural gas probably doesn’t peak until 2030,” says Rohner. “It’s going to continue growing across the United States.”

Over the past decade, natural gas prices have fallen dramatically compared with those of other fossil fuels, making it a relatively cheap fuel source. One concern about buildings constructed without access to gas lines is that if electricity prices spike, building owners and occupants could end up stranded with only one power option—an expensive one—whereas gas could offer a lower-cost choice.

A study by the American Gas Association found that extensive residential building electrification could drive peak power demand much higher, although electrification advocates criticized some of the report’s assumptions.

Another impediment to going all electric: the US electric grid isn’t yet up to the task.

The grid needs to be upgraded to accommodate changing use patterns as use of electric cars becomes more widespread and building electrification increases, according to the Union of Concerned Scientists.

Batteries are one solution to changing power needs in an all-electric-buildings scenario, but they are ill-equipped to handle demand surges because the amount of power they can store degrades over time and the size of the array needed to meet peak demand could be economically prohibitive. The toxic chemicals they are made with can also be an environmental hazard if the batteries aren’t properly recycled.

What’s Happening Now

Urban developers are already implementing features like in-garage electric vehicle charging stations and electric water heaters to attract eco-conscious residents.

Tesseract Capital, an active West Coast commercial real estate investor, redevelops properties with advanced appliances, smart thermostats, photovoltaic solar panels, and other tools where possible but has seen the difficulties of connecting to the electric grid.

“The move away from natural gas will be of significant long-term benefit to eco-friendly housing,” says Derek Flores, Tesseract Capital’s president of development and construction. “But we need a parallel development of electrical infrastructure improvements—transmission lines, transformers, storage, and the like. The costs and timing must be carefully considered as steps are taken towards renewable energy.”

In August 2019, Texas experienced dramatic price swings and came to the “brink of blackout” from grid issues and slower-than-normal winds driving its wind farms.

“More and more developers are going to have to employ advanced energy strategies to sell homes,” Rohner says. “Eventually, all homes are going to have to be ready to hook up an electric vehicle. The home—if not most commercial buildings—is going to become much more of a distributed energy market. The future of the country’s energy needs will follow the three Ds: distributed, decentralized, and decarbonized.”

“That might be five to 10 years off, but it’s coming,” he adds. “There’s no question about that.”

We’re Here to Help

To learn more about this topic and how it might benefit or affect your business, contact your Moss Adams professional.